Killing the St. Lucie River

How Politics and Wasteful Projects Have Rendered a Great River Unfit for Human Contact, Damaged the Economy and Destroyed Plants and Wildlife

A Special “White Paper” Report by the Rivers Coalition Legal Task Force

Synopsis: Today’s Crisis

The St. Lucie River is now damaged to the point that it is a human health hazard. Fish and wildlife are virtually gone. Recreation on the river has nearly ceased. An historic river has been judged by the Florida Health Department to be unsafe for human contact.

Lives and the economy are affected by this ongoing disaster as never before. Legal action is no longer optional, it is necessary to obtain adequate changes in water management. There must be short-term recovery reforms while longer-term plans and projects of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan and other programs are supported and implemented.

Lake Discharges at Fault

Countless community leaders are expressing outrage at the ruination of the St. Lucie caused by unnatural discharges from Lake Okeechobee. These discharges total more than 100 billion gallons a year of polluted fresh water that is sent to sea through Martin County. An even larger quantity is discharged to the West Coast.

The multi-county Treasure Coast Regional Planning Council adopted a resolution (Sept. 2005) concluding that “persistent discharges from Lake Okeechobee have caused critical conditions in the St. Lucie River, Caloosahatchee River, Indian River Lagoon and Lake Worth Lagoon” and that “immediate actions are needed…to resolve the current crisis.”

We find that the Army Corps and Water Management District must take the following steps to eliminate or radically reduce the discharges from Lake Okeechobee:

- Maintain much lower water levels in Lake Okeechobee

- Increase water storage in the Everglades Agricultural Area

- Authorize the Indian River Lagoon component of CERP and the entire program

- Accelerate development and purchase of storage areas north of Lake Okeechobee

- Complete the Modified Water Deliveries to the Everglades National Park

- Reduce phosphorus loading into the watersheds.

Until reforms are accomplished, the estuaries are certain to receive discharge onslaughts that will degrade the waters during many if not most years. The community should not be misled, it should be noted, by brief interludes of cleaner water when discharges periodically are curtailed. These slightly better conditions may be likened to being in the calm eye of a discharge hurricane. More problems lie just ahead.

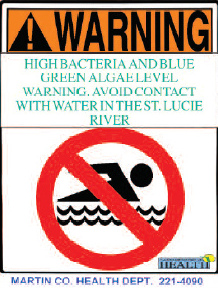

As the crisis reached its worst-ever point this year, health department warnings have been posted at public areas banning swimming, and in all capital letters stating: AVOID CONTACT WITH WATER IN THE ST. LUCIE RIVER.

A poster produced by state authorities states that swimming in water with toxic blue-green algae can cause “skin rash, runny nose and irritated eyes,” and swallowing such water can cause “vomiting or diarrhea, affect your liver and poison pets.”

A poster produced by state authorities states that swimming in water with toxic blue-green algae can cause “skin rash, runny nose and irritated eyes,” and swallowing such water can cause “vomiting or diarrhea, affect your liver and poison pets.”

Numerous citizens have reported medical problems after contacting the St. Lucie waters. Fortunately, the problems are lessened by the fact that many people “know better than use the water”, so activity is, sadly, minimal.

Resorts have cancelled use of the river for activities such as board sailing, swimming, kayaking, boating and use of jet skis. Most fishing activity also has been curtailed.

Among life forms severely impacted are Johnson’s seagrass, oysters, manatees and dolphins.

New “Recovery” Plan Announced

Recently, in response to a growing outcry against estuary and lake conditions, government officials announced an “action plan” called the Lake Okeechobee and Estuary Recovery (LOER) program.

The LOER plan states that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “will revise the lake regulation schedule by December 2006…to achieve lower lake water levels and reduce high volume discharges to the estuaries.”

Actual implementation of such a schedule may come much later, however, and if existing models are utilized in designing it, the result may not significantly reduce high-volume discharges to the estuaries. LOER promises fewer discharges “while not impacting current water supply demands” (the Everglades Agricultural Area).

In short, the sugar industry will get just what it wants, no more, no less.

Other components of the LOER plan basically call for acceleration of projects that have been in various stages of development for many years.

Overall, we find that the LOER plan and other existing works will not sufficiently reduce the east-west canal discharges or resolve the continuing crisis in Lake Okeechobee itself.

Background

The drainage basin of the St. Lucie River is 775 square miles and includes the majority of Martin and St. Lucie Counties and a small portion of Okeechobee County. This land area along the lower east coast of Florida has largely avoided the development extremes in Palm Beach County and further south. As a result, the St. Lucie River basin still includes significant expanses of natural flood plain and wildlife habitat.

However, the drainage basin, and the River itself, have undergone dramatic changes from their original natural character. Lands in the western basin that once drained north to the St. Johns River and south to the Everglades now drain directly to the St. Lucie River via canals C-23, 24 and 44. Lake Okeechobee drainage that formerly went south to the Everglades was redirected to the St. Lucie River via C-44.

These drainage works are directly responsible for the degradation of the River over the past 60 years, and its current status as unfit for human contact.

History

The St. Lucie River reportedly was named Santa Lucea (after the local settlement of that name) by Spanish explorers in 1565. Santa Lucea was eventually abandoned, with the next significant attempts at colonization beginning with land grants in 1803.

By the 1920's, with a permanent St. Lucie Inlet open, extraordinary fishing helped fuel the first land boom. Along with the land boom came reclamation drainage for agriculture and flood control projects. The Okeechobee Waterway (C-44) connecting Lake Okeechobee to the St. Lucie River was completed in 1937. Major Federal flood control works in the area continued through the 1960's with major canal construction, including expansion of C-44, C-23 and C-24.

Environmental Resources

The St. Lucie River falls in the first subtropical zone encountered moving north to south on the eastern seaboard of the United States. Historically, the major tributaries to the St. Lucie River, the North and South Forks, provided a relatively constant supply of fresh water from extensive wetland systems within the tidal basin. This stable inflow of fresh water supported a unique and thriving estuarine habitat which served as nursery grounds for a huge variety of fishes and benthic organisms. The St. Lucie River was even more productive and diverse than the Indian River Lagoon, which today is the most diverse estuary in North America.

The North Fork of the St. Lucie River branches into Five Mile and Ten Mile Creeks. These two creeks are largely channelized now and retain little of their original character. The North Fork itself, and the flood plain surrounding it, have remained largely undeveloped. This area of the river epitomizes the jungle character of subtropical rivers prior to man’s major influences.

The winding South Fork of the St. Lucie is in a largely undeveloped basin, and retains qualities which have led to its proposed submission for Wild and Scenic River status. Both the North and South Fork natural areas remain as examples of the natural character that once existed in Florida estuaries. Some of the time they support a variety of bird rookeries and wildlife such as alligators, turtles, bobcats, and occasionally a panther sighting.

While the twisted and braided portions of the original North and South Fork flood plains retain much of their native character, the majority of the River occurs in the wider portions as it broadens toward the coast. The broad lower reaches of the North and South Fork historically supported sea grasses and oyster beds and extraordinary fisheries ranging from black bass to snook, tarpon, goliath grouper and other species. The two broad forks join at Stuart, wrapping the city on three sides by river, and then proceed through the middle estuary to the tip of the Town of Sewall’s Point where the St. Lucie River joins the Indian River Lagoon at its junction with the St. Lucie Inlet, connecting to the Atlantic Ocean.

Until the past decade these lower reaches of the St. Lucie River continued to be major opportunities for boating, water sports, fishing and, on the offshore reefs, recreational diving and sport fishing.

Today, the River is in the worst condition in its known history.

Current Public Policy

The gradual decline of the St. Lucie River is well documented through decades of local complaints and concerns. There is widespread agreement within the scientific community that estuaries such as the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie cannot maintain a healthy ecology when salinity fluctuates between extreme fresh and saline conditions. Computer modeling suggests the Caloosahatchee requires freshwater augmentation while the St. Lucie does not. Both estuaries require protection from excessive wet season freshwater flows in order to survive.

Excessive wet season freshwater flows to the St. Lucie originate from two places: The local drainage basin including canals C-23, 24 and 44; and Lake Okeechobee. Local governments have poured millions of dollars into local stormwater quality and quantity projects since 1995 to improve the quality and timing of urban stormwater discharged to the River. Every local government in the St. Lucie River Basin has a funded an active Stormwater Utility.

Improving river basin drainage quantity and quality outside the urban areas is the purpose of the Indian River Lagoon Restoration Plan (IRL Plan), in the Water Resources and Development Act (WRDA) 2005.

The IRL Plan includes major water storage reservoirs totaling 127,000 acre-feet, and over 10,000 acres of man-made marshes for stormwater treatment. It also includes 7.9 million cubic yards of muck removal from the St. Lucie River. The water storage and marsh areas will be surrounded by another 90,000 acres of uplands and restored wetlands, creating a greenway that connects the Everglades with the St. Johns River marsh and Kissimmee Valley. These facilities will modify the existing local drainage patterns to the River so that some water quality problems are corrected.

Estimated cost is $1.2 billion. When completed, these improvements will reduce harmful freshwater drainage to the St. Lucie Estuary, while adding major environmental value both within and outside the River.

Doing their part, and then some, Martin County voters approved a special one-cent sales tax to purchase land needed for the IRL plan, totaling more than $50 million to date.

The IRL Plan: Good But Not Enough

Unfortunately the IRL Plan cannot by itself return the River to good health.

Lake Okeechobee presents an entirely separate problem. The 1998 “Yellow Book” that outlines the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan reports 55 months of excessive freshwater flows from Lake O into the St. Lucie over the 31-year period of record, or about 15% of the time. Since January 1, 2003, we count 33 weeks of excessive flows from the Lake, or 23% of the time.

Even worse, the most extreme high flow events, that had happened once in the 31-year period of record, have now occurred five times in the past eight years.

The consensus is that Lake Okeechobee must be managed at a much lower average water level in order to save the failing Lake ecosystem, and protect the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee Estuaries from repeated damaging high rate freshwater releases. The present Lake Regulation Schedule, WSE, does not include operational tools for effective management at lower lake stages because it is biased toward storing water, not releasing it safely. Touted as the “Water Supply and Environment” schedule, it has proven effective for water supply, mainly to the Everglades Agricultural Area, but is an abject failure for the environment.

South Florida Water Management District (SFMWD) data show that average annual water demand on Lake Okeechobee from all users is about 800,000 acre-feet. The annual Lake storage required to serve this demand is about twice as much water, or 1.6M acre-feet, due to evapotranspiration losses from the Lake. The Lake area is about 470,000 acres. Annual storage of 1.6M acre-feet equates to about 3.4 feet of water over the Lake during the average year.

The average annual water supply for all potable uses from the Lake appears to be about 40,000 acre-feet, or 5% of annual irrigation use. The greatest potable water demand on Lake O during a single twelve month period during 1971 through 2002 was reportedly 310,000 acre-feet in 1988-89. The average annual potable usage during five drought years between 1971 and 1998 was 140,000 acre-feet. As long as the Water Conservation Areas are near normal seasonal stages, no Lake O water is used by coastal utilities.

Sugar production is by far the largest consumer of irrigation water from the Lake. Sugar acreage in the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) expanded from 175,000 acres in 1971 to 465,000 acres in 2002. Statistical analysis of sugar production and rainfall in the EAA since 1971 shows there is no relationship between sugar yield (tons per acre) and varying rainfall.

Sugar-Farming: No Shared Adversity

Thus, sugar farmers in South Florida, unlike most farmers in the rest of the world, are not affected by wet or dry rainfall years. The small yearly variations in sugar production, and gradually increasing production per acre over the past three decades, show that both irrigation and drainage for the sugar industry have been maintained at or near perfect conditions.

During the most extreme droughts over the past thirty years, when water supply restrictions have been implemented by SFWMD, as little as 250,000 acre-feet of Lake waters have been supplied to the EAA for irrigation. SFWMD published extensive technical reports of drought conditions during the years 1970-71, 1981, and in 1988-90 (we are still awaiting final reports for the most recent drought of 2000-01). Lake Okeechobee levels dropped below 10.5 feet and as low as 8.9 ft. during the 2000/2001 drought. Even in these most severe droughts, we find no data that relate a shortage of Lake irrigation to a loss of sugar production.

The Lake regulation schedule, most recently modified in 2000, is driven by two major competing objectives. The Army Corps of Engineers is concerned with flood control. SFWMD is concerned with holding Lake levels high enough for water supply. Holding the lower levels too high results in later flood control releases to the Estuaries when inflows cause rapid increases in Lake stage.

Lake stages are maintained higher than necessary because theoretical models predict economic losses by agriculture when irrigation supplies are inadequate. SFWMD publications predict more than a hundred million dollars of losses to the sugar industry during droughts due to inadequate water storage in the Lake under the WSE schedule. However, there is no actual economic loss recorded during the period 1971 through 2002 to corroborate these theoretical predictions.

Theories That Defy Reality

Upon detailed analysis, we find that SFWMD predictions of economic losses to agricultural interests from drought are based upon a theoretical model of water shortfalls, which in turn is based on theoretical evapotranspiration predicted for optimum crop production.

For example, the SFWMD Lower East Coast Water Supply Plan (Appendix E) reports supplemental irrigation requirements for EAA sugar in a one in 5 year drought for 440,000 acres of sugar production are 539,000 acre-feet. During 2000/2001, the most severe drought year in the entire period of record, SFWMD supply side management data show less than 300,000 acre-feet of irrigation water was actually supplied to sugar producers, or only 55% of theoretical minimum needs.

The Price of Keeping Sugarland Dry

In theory, significant production losses should have occurred. In actuality, it was one of the five best years on record for sugar production.

In fact, the historic data show there has never been a loss of sugar production in the EAA due to a lack of irrigation water during the period of record. In only one year, 1981, lower production in tons per acre corresponds with a drought year. That particular year was further investigated by SFWMD, and slightly lower sugar production that year was reported to be associated with a winter freeze rather than a lack of irrigation water.

The root cause of the failure of Lake regulation to protect the Lake and Estuaries is the South Florida Water Management Model (SFWMM) used by SFWMD to model Lake regulation options. This model places the EAA in the center of all decisions by holding its water table 18” below ground. Holding over 600,000 acres of land at a constant water table, wet season or dry, forces the rest of South Florida to make up for seasonal fluctuations in rainfall for the benefit of the EAA.

This results in flooding the WCA’s during wet conditions, and flooding Lake O and the Estuaries nearly every year to provide the EAA unneeded irrigation storage for the dry season.

In the SFWMM model the Kissimmee River basin is not managed in concert with Lake Okeechobee with regard to water supply for consumptive users. The Kissimmee River and Chain of Lakes are treated as an independent point source input into the Lake, operated by regulation schedules adopted 50 years ago. The single largest water supply to Lake Okeechobee is not treated as a manageable hydrologic asset to the rest of South Florida, but as if Lake Okeechobee did not exist. The potential contribution of the Kissimmee Basin as an active and manageable component of Lake Okeechobee regulation has never been evaluated.

In 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2003-2005 Lake Okeechobee’s discharges of excess water resulted in significant harm to the Estuaries. SFWMD considers this harm acceptable if the Estuaries can recover within 1 or 2 years. This is “shared adversity” according to SFWMD policy. Yet, there is no evidence that anyone above or below Lake Okeechobee shared any adversity at all, much less a level of adversity that takes 1 or 2 years to recover from.

Biased Models Favor EAA

Given the pattern of the past eight years, it is obvious that the Estuaries will never recover under the present Lake O management plan. Further, the SFWMM computer model used to evaluate alternatives is so biased toward the EAA it cannot provide a result that would protect the Lake and Estuaries.

High water levels maintained through the 1990’s brought Lake Okeechobee to the brink of environmental disaster. High levels in 2003, 2004 and 2005 have again damaged the Lake. The Estuaries have been pounded repeatedly with high level discharges from the Lake due to excessive high stages. We cannot afford to wait for the CERP to correct all of our problems. We need immediate help for the Lake and Estuaries.

The Solution

A new Lake regulation schedule with water supply priorities based on real risks and benefits rather than theoretical models of evapotranspiration and crop yields must be developed without delay. The Kissimmee Basin should be a more actively managed part of the water supply system within the SFWMD. A new model is required to adequately evaluate these options

The practical goal of such a new schedule would be less water stored in the Lake and Kissimmee Basin on average, making more storage available for wet periods, enabling more gradual movement of water through the entire system during wet conditions and more flexibility in drawing the entire system down during dry periods. Kissimmee lakes should be allowed to fall to lower stages more often so that “extreme drawdowns” for their ecological health are part of a regular ongoing management plan rather than another risk factor for Lake O and the Estuaries, such as the recent Lake Toho drawdowns.

Drainage of the EAA also should be reviewed. Providing the EAA perfect drainage requires pumping all excess water into the Water Conservation Areas. This in turn restricts capacity in the WCA’s for release of excess Lake O waters. In 2003, for example, rainfall in the EAA and WCA’s was about equal to the annual average, yet all the WCA’s were above regulation schedules and excess Lake O water could not be sent south to the Everglades. This pattern has persisted through 2005.

More active and frequent use of low level discharges to the Estuaries may also be required in order to avoid both pulse releases and high stage, large continuous releases. These should be reevaluated for both the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Estuaries. The Caloosahatchee can accommodate larger quantities of fresh water over longer periods of time than the St. Lucie can. The minimum flows now directed to the Caloosahatchee are not adequate for its optimum environmental health, and this should be reevaluated as part of improved Lake O management.

A continuous release of only 500 cfs distributed among various outlets to tide, according to their tolerance for salinity variations, would reduce the yearly average Lake O level nearly one foot. At the same time, a lower level pulse schedule for both Estuaries should be evaluated. The Caloosahatchee in particular may benefit from more variable pulse flows, due to nutrient and algae bloom issues, while even the existing Level I pulses damage the St. Lucie River’s health.

A new Lake regulation schedule must include provisions for continual adjustments as CERP water supply and water diversion projects come on-line, moving the Lake and Estuaries further toward environmental restoration goals and away from destructive impacts of the present water supply and drainage policy.

The Florida Constitution (Section 7, General Provisions) states:

“It shall be the policy of the state to conserve and protect its natural resources and scenic beauty. Adequate provision shall be made by law for the abatement of air and water pollution…for the conservation and protection of natural resources.”

While this straight-forward policy directive apparently is non-enforceable in a court of law, it should weigh heavily on the actions of public officials and agencies.

Conclusion

Considering all factors, we must demand that action be taken to stop all discharges from Lake Okeechobee to the St. Lucie Estuary, except during extremely unusual true emergencies. It is clear that government agencies have a variety of tools and options available to achieve this goal.

The economic value of a restored and protected estuary and Lake ecosystem will far outweigh any benefits given to subsidized private interests through the artificial drainage system.

More importantly, our children and grandchildren deserve a safe, pristine estuary teeming with life. That we must provide them.

--The Rivers Coalition Legal Task Force, November 2005

Homepage | How to Help | About Us | Newsletter | Events

Lawsuit | Media | Learn More | Links | Calendar | Contact Us

Copyright ©2006 - 09 Rivers Coalition

Web Design & Photography TiffanyRichards.com